I believe this is a truly excellent article explaining expansionary monetary policies and outlining the possibilities of unwinding quantitative easing programs. Eighteen global leading economists share their opinions.

Please read all the comments at Focus Economics here.

My part:

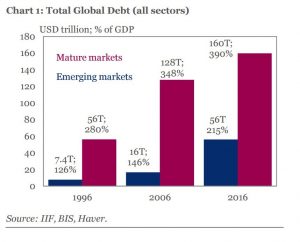

“The Federal Reserve is already seriously behind the curve. Reducing the balance sheet by $600bn after a $4.7 trillion stimulus and delaying rate hikes simply make the problem more difficult to solve as we approach a change of cycle and the central bank finds itself with fewer tools. The Federal Reserve should take advantage of the unprecedented demand for USD and the fact that macro drivers and corporate profits are improving to accelerate its unwinding of the stimulus. However, it seems comfortable ignoring the risks of perpetuating bubbles in financial assets. By being too focused on financial markets it becomes what I call in my book “Escape from the Central Bank Trap” a “pyromaniac firefighter” that creates a massive bubble and presents itself as the solution when it bursts.

The Federal Reserve could be raising rates and unwinding its balance sheet by $50-100bn every month now that demand for bonds and equities remains solid and the employment, inflation and growth data is improving, while earnings estimates are increasing. There would be more than ample secondary market demand for a solid sterilization program.

The ECB is caught between a rock and a hard place. It is on its way to reaching a balance sheet size of more tan 25% of GDP of the Eurozone and inflation expectations are falling, unemployment and slack are still high, proving that the problem of the Eurozone was never of liquidity and low rates. When the ECB QE started, excess liquidity was c€185bn and today it is close to €1.3 trillion. In the process, highly indebted and deficit-spending countries saved billions in interest payments,… but their imbalances remain and they have spent those savings and more, making it almost impossible for the ECB to taper and raise rates because high-deficit countries would be unable to assume it. But at the same time, the overcapacity of the economy is perpetuated and many countries are calling for further spending increases and widening deficits. The ECB, therefore, needs to give a stronger message to governments so that they accelerate reforms to reduce excess spending and improve growth, lower taxes. If the ECB starts a sterilization program and manages long-term rates adequately, it could successfully promote structural reforms, help spur growth and use that massive excess liquidity to keep bond yields low while governments improve their fiscal position. This would reduce the perverse incentives that some may have to increase imbalances just because QE is there. Furthermore, as the crisis is way behind us, the ECB’s purchases would be easily offset by real investor demand, as fundamentals improve. There is still time before Europe enters a dangerous “Japanization” process.”

Courtesy Focus Economics. Follow @FocusEconomics

Daniel Lacalle is Chief Economist at Tressis SV, has a PhD in Economics and is author of “Escape from the Central Bank Trap”, “Life In The Financial Markets” and “The Energy World Is Flat” (Wiley)

See more at: https://www.dlacalle.com/what-does-dr-copper-tell-us-about-global-growth/#sthash.AmZP9FEL.dpuf