“One thing I’m sure of, I’m in the deep freeze, cold turkey has got me on the run,” John Lennon.

After more than 20 trillion dollars of incorrectly-called “stimulus”, the addiction to monetary laughing gas has generated what a predictable, and generalized, drop in stocks and risky assets. Predictable as it was, it caught many of us – I included- by surprise because financial repression leads us to chase momentum on the evidence that prices surpass even the most aggressive analysis.

After more than 20 trillion dollars of incorrectly-called “stimulus”, the addiction to monetary laughing gas has generated what a predictable, and generalized, drop in stocks and risky assets. Predictable as it was, it caught many of us – I included- by surprise because financial repression leads us to chase momentum on the evidence that prices surpass even the most aggressive analysis.

Many analysts have rushed to search for “reasons”, from the wage increases in the US to the fear of inflation. Although, as in all corrections, there are many reasons, it is almost curious that few have commented on what I explain in Escape from the Central Bank Trap.

The disastrous policy of central banks has led economic agents to take more and more risk for lower yields, to increase debt because rates are low and to make almost everyone think that volatility had disappeared and risky assets could only go up. The need to “catch-up” with markets led many of us to believe we could do nothing else but add risk. And we discussed here the risks of accumulating imbalances.

Yet signs of excess could be found everywhere.

The European Union and Japan accumulated more than 7.5 trillion dollars in bonds with negative yields.

The Central Bank of Japan accumulated more than 75% of the ETFs of the Japanese stock market.

Greece’s two-year bond traded at a lower yield than that of the United States.

Argentina, a country that has defaulted more than six times in the last hundred years, issued a one-hundred-year bond at only 8% yield.

While many talked about “synchronized” growth, global debt soared to 325% of GDP, also in sync.

Investors went to buy indexed funds and passive management soared because “as everything goes up, at least I am saving in commissions.”

Emerging countries that were on the verge of bankruptcy only two years ago issued bonds at 4-5% yield.

This correction seen in the week of the stock markets and the synchronized sell-off in bonds and emerging markets have a clear explanation. While valuations had become too high and complacency with the bond bubble was extreme, market participants -inadvertently- were adding more to the same bet disguised in different asset classes: perennial asset inflation due to money supply growth. It is such an extreme bet that, throughout the week, the preferred bet despite the sell-off has been to accumulate positions in securities and bonds of companies and countries in difficulties to “catch the rebound” (according to Morgan Stanley).

There are reasons to be cautious and at the same time reasons to be optimistic.

Cautious because if the US 10-year bond, the lowest risk asset in the market, yields 2.85%, there is a brutal amount of paper from emerging markets with questionable dividend and bond yields which show an unattractive risk-reward. The “yield chasing” policy that we alerted at CNBC can create a risk of huge nominal and real losses. Not only is the differential with the lower-risk asset too low to hold on to those positions, but those bonds will probably fall in price as the United States and the US dollar strengthens its position as a safe haven.

While we must be aware that stock markets and risky assets were expensive we also can find opportunities when the sell-off is indiscriminate.

On the positive side, we are very far from an environment of huge imbalances like 2007 or 2011. Corporate profits are not increasing as much as some would like, and the risk of downward earnings revisions is important, but if you look at developed markets, most companies still beat estimates and deliver solid profits. In the US, in addition, the end of share buybacks is not happening. This means that, now, many strong companies’ securities are finally becoming too cheap to ignore for an investor with a mid-term horizon. I would focus on developed markets, though, because the risk of a sudden stop in emerging markets -abrupt end of the flow of capital- is not small, as more money returns to the US after the recent measures to facilitate repatriation.

The banks are not a systemic risk. We have seen core capital increasing (CT1) at almost 1% per year and banks have reduced their imbalances. This is not to say that everything is wonderful in bank land, but we are not in an environment of systemic risk or crisis similar to 2008. This provides buying opportunities as long as our thesis when buying is not to pray for science fiction inflation increases or expect central banks to take us out of our losses.

In 2017, stocks and bonds behaved aggressively, anticipating an extremely accommodating scenario for the global economy. The constant bombardment of consensus and the mainstream on the magical benefits of the monetary laughing gas and the omnipotent qualities of central banks has generated an excess of confidence in the markets. Countries on the verge of bankruptcy were financing themselves at negative rates and nobody was alarmed. Companies with atrocious earnings soared in the stock market and nobody was alarmed.

It had to take a slight warning in the US bonds to reminds us that money is neither free nor risk-free.

Now, opportunities appear. If we have not fallen into the central bank trap of believing in inflation by decree, in the expansion of multiples by magic and in the infallibility of central banks, we will find bargains and fundamental value.

At the annual meeting of the Eurohedge Awards in London a couple of weeks ago, an award winner said “an acceptance speech should never last more than a rally of emerging markets, so I will be very brief.” And so it happened.

Let us not worry too much about a correction. Let us focus on fundamental analysis, not the faith in magic.

Let us be aware that if everything goes up at once, it will also fall in unison. And let’s look for opportunities, which come in abundance … as long as they do not depend on another “shot” of laughing gas. Because that, as I explain in Escape from the Central Bank Trap, is over.

The next time you read how good central banks are because everything goes up a lot in markets, remember that their policies of manipulating the quantity and price of money are also the cause of these crashes.

As Warren Buffett said, “be fearful when others are greedy and greedy when others are fearful”.

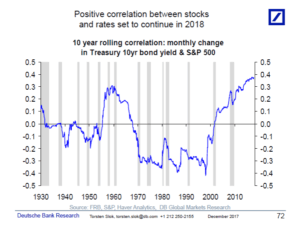

Chart courtesy of Deutsche Bank and Torsten Slok.

Daniel Lacalle is a PhD Economist, author of Escape from the Central Bank Trap and Life In The Financial Markets. He is Chief Economist at Tressis