(This article was published in Cotizalia on July 1st 2012)

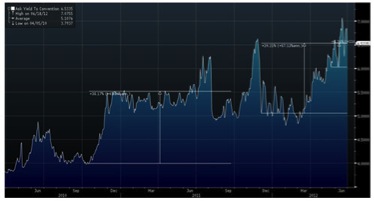

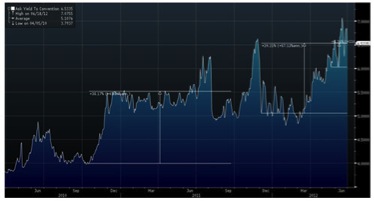

The EU summit concluded with a surprise note. The strategy of Spain and Italy to corner their partners has been a masterstroke and it buys both countries time. Unfortunately, these agreements have had a very modest impact on the Spanish 10-year bonds, still at 6.25 percent, and the spread to the German Bund, which is around 475 basis points.

Why? Because it is still a patch. As someone in Twitter noted ” A decisive solution, using a fund that doesn’t exist to buy debt that won’t be repaid via a mechanism that hasn’t been agreed.” I’ll try to explain it as simply as possible going through the main comments from readers.

Why more uncertainty?

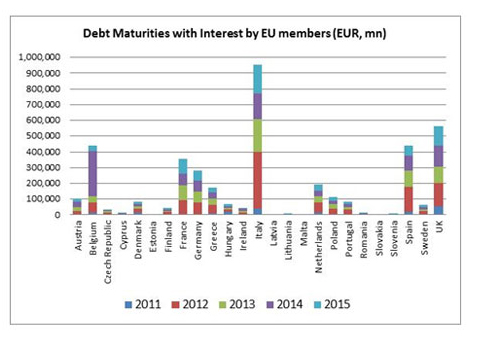

It doesn’t matter which entity we think will provide the funds, be it the European Central Bank, the European Financial Stability Facility or theEuropean Stability Mechanism. They will have to finance themselves in the secondary market, with capital from foreign investors, SWFs, etc. These investors see that the legal structures, mandates and limits of the European mechanisms are discussed, threatened and redesigned almost every month, generating tremendous uncertainty. Therefore, neither the EFSF nor the ESM, when approved, will enter the benchmarks used by funds to decide where to invest.

In short, threatening legal structures that underpin these mechanisms scares investors away, precisely when they are most needed. Would you invest in a fund in which each month the managers threaten to change the prospectus?

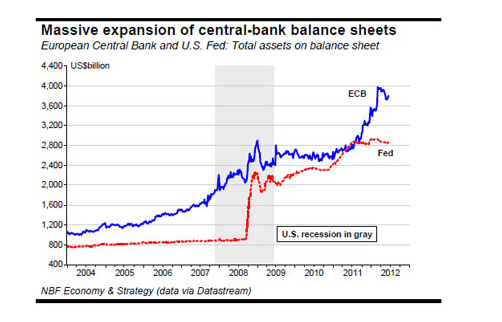

We have discussed in previous weeks the enormous difficulties faced by these mechanisms. The ECB’s balance sheet already exceeds 30% of the GDP of the Eurozone, compared with 20 percent of the US Federal Reserve or theBank of England. The European countries that contribute to these mechanisms and the ECB are extremely indebted. In addition, as time passes,there are less “net contributors” because the number of troubled countries grows. Portugal, Greece, Ireland, Spain … and Cyprus, which after four years in the EU, needs a bailout of €10 billion with a GDP of 18 billion.

France already has 89 percent public debt to GDP, Spain surprised negatively on Tuesday with a much higher deficit than expected, German default risk rose 30 percent in a month and meanwhile almost all eurozone economies are in recession or stagnation, while the vast majority of those countries are increasing their debt.

There is no money to continue this “ostrich strategy “of avoiding tackling the debt problems and kicking the can down the road in an EU that feels more isolated from the rest of the world each day.

Why bond spreads keep widening

The spread of the Spanish bond with the Bund is a reflection of the secondary market, ie the investor appetite adjusted by a certain risk. We can complain and make European entities intervene, but if markets don’t see reliable, verifiable and sustainable economic figures and an improvement in the ability to repay debt, investors will not buy bonds. That is why on Friday we saw fund flows of 3 to 1 better to sell.

Imagine a quoted company that is posting weakening results and a major shareholder buys 5 percent in a defensive move. The share price might stabilize for a few days, but then it continues to fall because institutional investors still do not trust the strategy and the profit generation ability of the company. We see the same effect on bond yields after the placebo effect of ECB purchases. Bond yields rise again, due to lack of confidence.

Grand public statements and good intentions are not enough. Until Spain publishes figures showing clear and sustainable improvement of credit qualitywe will not see bond yields fall.

Are markets attacking us?

Investors are not buying Spanish debt. That is not attacking. It is not buying. We should analyze why an investor in bonds, which seeks the lowest risk and the longest duration, prefers to buy bonds at 0 percent yield, the Germans or Swiss, rather than bonds with 6 percent yield, the Spanish. They avoid high yield bonds because they worry more about whether the principal is ever going to be repaid. As Jim Rogers used to say “I am more interested in the return of my money than the return on my money”

With the level of uncertainty about Spain’s public finances, investors feel that 6 percent is not an attractive risk-reward. Spain has destroyed its credibility with changes in deficit figures, broken promises and hidden data for years, and now it has to bring back confidence with facts.

Bond investors do not distinguish between one political party or another, or one government or another. It is a sovereign matter. And if the state doesn’t meet its own targets, investors don’t risk their capital. Would you do it? Would you invest in the debt of a country where targets are not met or are made up? This is what Spain has to solve, now. slashing expenses.

Doesn’t Spain have less debt than Japan?

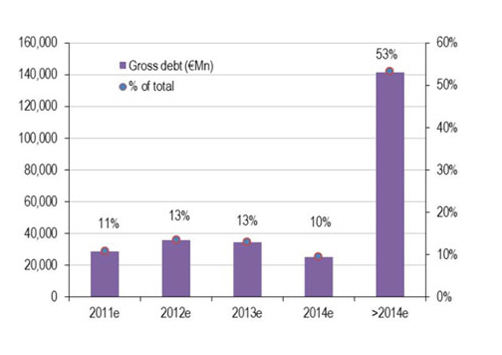

The spread of Spanish bonds is not high by coincidence or injustice. As a country, Spain always talks of its low debt to GDP, which is a misleading indicator, as GDP, for example, can be artificially inflated by borrowing to build useless things -phantom airports, ghost cities, etc.

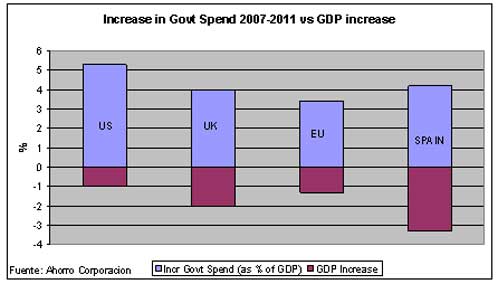

What matters to investors is the deterioration of the public accounts, revenues falling and costs rising. Spain’s debt has doubled between 2008 and 2012 but the country has not done enough to stop the escalation of spending while tax revenues coming from the “housing bubble” disappeared. But the expenditures have remained untouched, most of all subsidies and bureaucracy. Spain had three major bubbles: Debt, Housing and State size. Of those three, State size is the one that has not been burst.

Imagine having a credit card for which one pays interest. If expenses double, but income stagnates, first one sees the interest rate rise, and if expenses don’t fall the credit card will be cancelled. And this does not mean that the issuer of the card is “attacking”, it just means that the card holder becomes an unreliable debtor.

Many will say that a country is not a credit card and that “we deserve” to be funded at lower costs. Fine, then, as a country, we should do what households and sensible companies do. Cut expenditures.

Intervention, let’s go

What happens when the credit card is cancelled? That one has to go to a lender of last resort that will solve the liquidity problem, but will demand cuts and high interests. Like those TV ads that say “reduce your monthly payments”, “we consolidate debts into one comfortable monthly payment”… at exorbitant interest rates and with severe penalties.

The problem of using the word “bailout” or “intervention” is that it has a positive connotation, almost humanitarian. I would recommend that when you hear the word, change it in your brain for “mortgage” and when you hear ECB think of “lender”. It shows a completely different meaning.

Some readers tell me they prefer an intervention than keeping our corrupt politicians. I do not know what to say. Changing politicians who have been elected to bring others who are not elected from Brussels? I am not sure, particularly when the latter have a track-record as poor as that of our own leaders.

Blame it on Germany for financing our real estate bubble

As a Finnish member of parliament said to me, “the fact that I have lent to a friend €1,000 and he has wasted the money in parties does not mean that I have to continue lending him or that he doesn’t still owe me my money”. Responsibility must be shared, but donations should not be expected.

But what if we are rated junk bond?

Rating agencies, I’ve said it many times, act always late and poorly. With Spain, investors have assessed its credit risk well below what rating agencies said since March 2011 at least. I always say that a rating agency is an entity that charges Paul McCartney to inform him that the Beatles split up.

First, Spain is not junk bond. But the risk of downgrades cannot be tackled by promising income that never comes, or by giving excuses for poor data, as any rated quoted company can tell. It is tackled by cutting costs and showing better numbers than estimated.

But if we cut spending, we lower GDP

Sure, let’s put more debt into the economy to build useless things until we have the GDP of China and let’s see how we do.

Of course cutting expenditures lowers GDP, but it also slashes the deterioration of our debt problem by a bigger percentage. Spain needs to cut political spending, duplicative administrations and unproductive debt that only generate impoverishment. We are talking of tens of billions per annum.

Print money?

It’s a unanimous cry. Let’s print money. The ECB must buy the debt of our wasted years and monetize it, creating inflation. Let’s do like the United States which “only” has a debt of $50,500 per citizen.

Print money in the EU, when the euro is only used in 25 percent of global transactions would generate high inflation. To begin with, we would have to see if our partners accept to drown the ECB in more debt. But I am surprised that people cry for inflation mentioning an “adequate” level of 5 percent-official, as real inflation would be 8 to 9 percent. I am shocked to hear people calling for their own impoverishment to allow the government to continue spending recklessly. If citizens think that raising VAT is a disgrace-and it is-inflation is the same, but “undercover” and cumulative.

Then there is no solution

Of course there is. Cut spending, duplicative administrations, subsidies and grants, be a serious country, open the doors to free market, and stop thinking that everything is arranged in the Eurozone web of cronyism, patronage and debt.

This week I wrote an article in the Wall Street Journal detailing the four points which, in my opinion, would help Spain to reduce bond yields. None of those points is to “solve a debt problem with more debt,” and the agreement of the EU is exactly that. It gives Spain and Italy time to accelerate and deepen reforms, but is nothing more than a loan.

Of course Spain will be helped and the country will emerge from this mess, but it will not be by going “back in time” like Huey Lewis & The News. It will be through cuts in spending and liberalizing the economy.