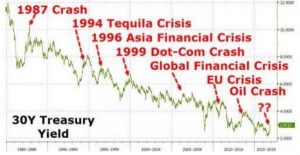

This week we heard the Governor of the Central Bank of Japan warn that low interest rates are sowing the seeds of the next crisis, which made me think of the pyromaniac fireman term I explore in “Escape from the Central Bank Trap”.

This week we heard the Governor of the Central Bank of Japan warn that low interest rates are sowing the seeds of the next crisis, which made me think of the pyromaniac fireman term I explore in “Escape from the Central Bank Trap”.

It is, at the very least, hilarious that the governor of the same Central Bank that already accumulates 55% of Japan’s ETFs and 42% of Japan ‘s debt , in addition to keeping rates at zero for more than fifteen years, talks of low interest rates as if they were a UFO that has fallen unexpectedly from the sky. Who cuts interest rates to unsustainable levels, completely disconnected from the real risk? Central banks themselves.

Of course, there is always someone who will say that central banks cut rates and increase money supply because markets demand it. Oh, please. It is a fallacy that the governor of the Russian central bank explained in an excellent interview on CNBC … If low rates were requirements from companies and markets to invest more, real productive investment would have skyrocketed in the past 600 rate cuts, and it did not.

What happens is that central banks mistakenly assume that there is a problem of demand and not of overcapacity and they assume a ratio of savings to investment that their teams deem too high because they use a bubble period as base. Central banks end up seeking to perpetuate economic imbalances by blaming the decline in investment on an abnormal behaviour of the private sector. And it is incorrect. Companies do not invest as much as the bureaucrats would desire -because invest, they do- because there is no need.

Thinking that a group of politicians and academics in a central bank know more about the required rate of investment than the private sector is pure lunacy. They do not have more or better information about the economy than companies putting their money at risk.

In a devastating article, a former member of the Federal Reserve recently warned that systemic risk in the markets has multiplied because of the actions of central banks. The mainstream academics who populate the decision-making bodies of central banks ignore financial risk and do not understand the distortions they create in the market.

That is the problem of the “pyromaniac firefighter” policy of central banks. Its objective is not to avoid a crisis, but to perpetuate the bubbles looking for inflation at any price. For this, they use the excuse of “employment” because if they said their actions aim to”inflate financial asset prices” it would look bad. As if buying bonds created jobs. Stimulating bubbles destroys a lot more jobs than it creates, when they burst. And they do.

All this is irrelevant to central bankers.

Junk bonds at the lowest rates of the past 35 years? No problem,”because there is no inflation”.

Government bond yields at completely unjustified levels compared with the solvency of States? No problem,”because there is no inflation”.

A central bank buys up to 10% of a bankrupt European country’s total debt? No problem, “because there is no inflation.

Bad loans refinanced to infinity? No problem, because “there is no inflation”.

But there is … A huge inflation in financial assets that has generated the largest bond bubble in history.

Now, inflation has arrived… And -oh, surprise- we find that central banks are trapped and cannot stop their policies. The Federal Reserve says that there is uncertainty about Trump’s fiscal policy … Surprising, because the Fed had no “uncertainty” about the wonderful estimated impact of monetary policy, even if they revised their growth expectations lower every year.

Ignoring bubbles is not new. I invite you to search for a single comment from central bank governors warning about the housing or internet bubbles… None. They justify them as a “new paradigm” and continue fuelling the fire.

It is not a coincidence that these mainstream academics mentioned before ignore financial risks while fund managers and real investors identify them. Almost no academic has ever suffered from denying a bubble. And, as Paul Romer showed , there are many perverse incentives to defend any policy adjusting the analysis to the desired result. I recommend you to read the numerous “it would have been worse” papers that appear every time monetary policy fails.

In Europe, at least, we have a president of the ECB who constantly warns that “monetary policy does not work without structural reforms”, but no one listens. Faced with the evidence of multiplying risk, the only thing that mainstream academics can articulate is to recommend carrying out a much more aggressive policy, to generate a government bubble on top of the financial one. As if no one had thought about it before.

The pyromaniac firefighter keeps these bubbles by manipulating the cost and amount of money and, when it fails, the blame – do not doubt it – will be of “the markets”. “Take risk, nothing happens, the central bank supports you” and then “it’s you, you took too much risk.”

The solution? “Solve” it with a few thousand pages of regulation. Sure, the problem is “regulation”, not artificially low rates and financial repression forcing investors to take more risk for lower returns. Sure, the problem is “regulation”, yet the laws in Europe state that lending to governments has no risk. No amount of rules and directives can mask the lunacy of zero interest rate policies and saying that government borrowing has no risk.

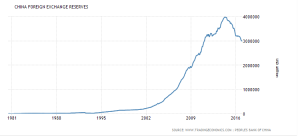

Data for December show that, in Europe, there were € 78.2 billion of outflows in debt. Foreign direct investment outflow was €52 billion (according to BNP). The fragile European recovery may suffer a major setback if the monetary laughing gas continues and, above all, if the imbalances that can lead to a major crisis remain. The financial system that was demanding and applauding “expansive policies” now sees in horror that this policy sinks margins and banks’ solvency.

The exit of this huge bubble will not be easy , because central banks believe they have many “tools” to combat deflation and inflation, but they have no clue how to fight stagflation. The pyromaniac who started the fire in the basement, saying that a few flames were not bad because the building was too cold, will now present itself as the fireman to control the disaster.

Daniel Lacalle. PhD in Economics and author of “Life In The Financial Markets”, “The Energy World Is Flat” (Wiley) and forthcoming “Escape from the Central Bank Trap”.

Image courtesy Google Images

This circle is happening in all countries .

This circle is happening in all countries .