The biggest mistakes in analysing macroeconomic data is to assume causality to factors that are just catalysts.

Don’t blame the Fed or Trump. That is just noise. The problem of emerging markets is largely self-inflicted and comes after years of raising imbalances, both at a trade and fiscal level, based on impossible expectations of growth and demand.

The Federal Reserve has warned for two years about rising rates and policy normalization. Yet governments ignored this and continued to increase imbalances as well as rising debt in US dollars.

Governments always consider that economic problems come from lack of demand, and they assign themselves the task of “correcting” that wrong assumption by massively increasing deficits and using monetary policy well beyond any logical measure.

India’s rising populist policies are part of the nation’s current problems.

Recent data is quite concerning.

August Nikkei Services PMI came at 51.5 vs 54.2 in the previous month, a 5% monthly drop.

Sovereign bond yields are at the highest level since 2014.

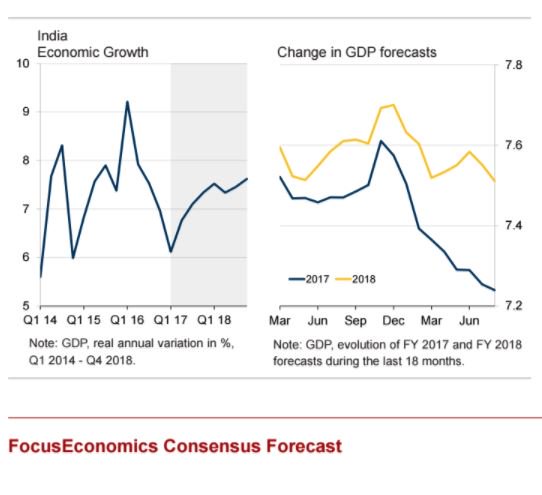

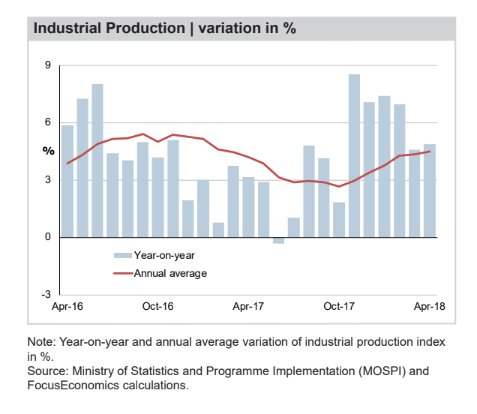

Industrial production and growth estimates are coming down (via Focus Economics).

Trade deficit in July 2018 was the highest since 2013. India’s trade deficit widened to USD 18.02 billion, the largest trade gap since May 2013, as imports jumped 28.81 percent.

According to Kotak Economic Research, India’s current account deficit is forecast to be the highest in six years. Under a $65 a barrel oil price scenario, the current account deficit is likely to be 2.4% of GDP, higher than in 2013-14. As oil prices rise, and imports soar, the overall balance of payments is moving into larger deficits than expected, as capital inflows weaken and are unable to current account deficit.

Another warning comes from the maturities in foreign exchange. Nearly $220 billion of short-term debt, equal to more than half of India’s foreign exchange reserves, will come up for maturity in 2018-2019 fiscal year. Moody’s states that India is one of the countries that are least exposed to a rising US dollar. However, Moody’s did not expect the rupee to fall this much.

The average maturity of debt is close to 10 years and over 96 per cent of it is in local currency, according to Moody’s. However, it also notes the country’s low debt affordability. Given that the vast majority of debt is in local currency, the incentive to depreciate the rupee is very high.

Foreign exchange reserves remain acceptable, but are falling rapidly. From $426 billion in April to $403 billion in August, foreign exchange reserves are likely to suffer another dip as the rupee falls against the US dollar.

At the same time, 68% of fiscal deficit target for 2019 consumed in the first quarter.

India expects a fiscal deficit of 3.3% of GDP in 2018-19 that seems quite challenging, given the weakening of data and the rise in expenses. Deficit was revised up to 3.5% of GDP in 2017-18.

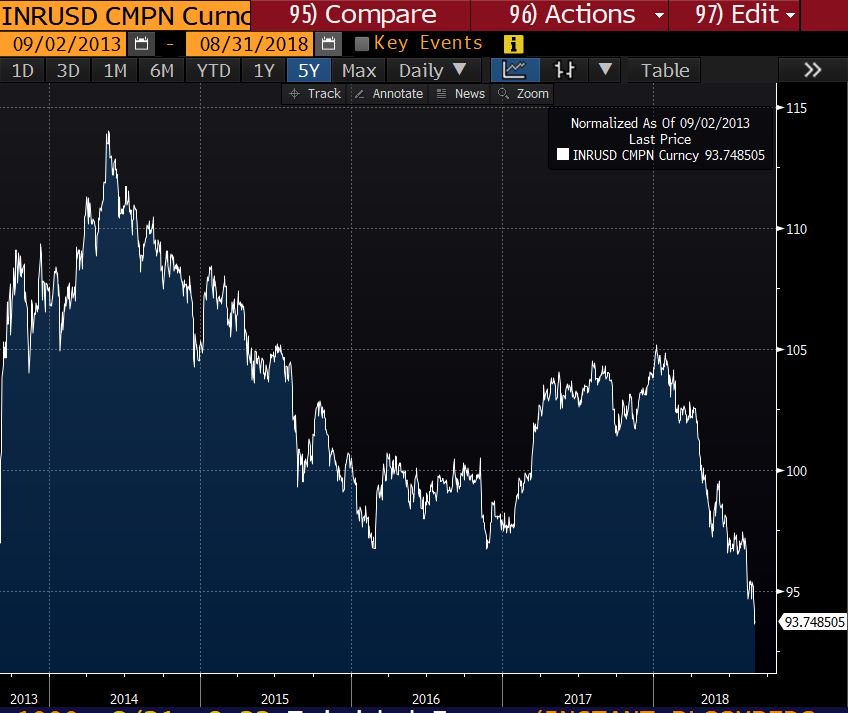

The combination of wider trade and fiscal deficits added to lower reserves makes the currency weaken severely. The rupee keeps plummeting to all-time lows vs the USD, as we explained in WIO News (watch).

India’s government usually solves this equation increasing subsidies and raising taxes. That combination will not work in a world that has lower tolerance for fiscal and trade imbalances and a risk-off scenario. Additionally, tax wedge is already a high burden. As Prateek Agrawal notes, “if one looks at GST and taxes on the affluent sections, India would rank as one of the highest taxed countries globally. For consumption, these sections are actually paying close to 60 per cent of the income as taxes).

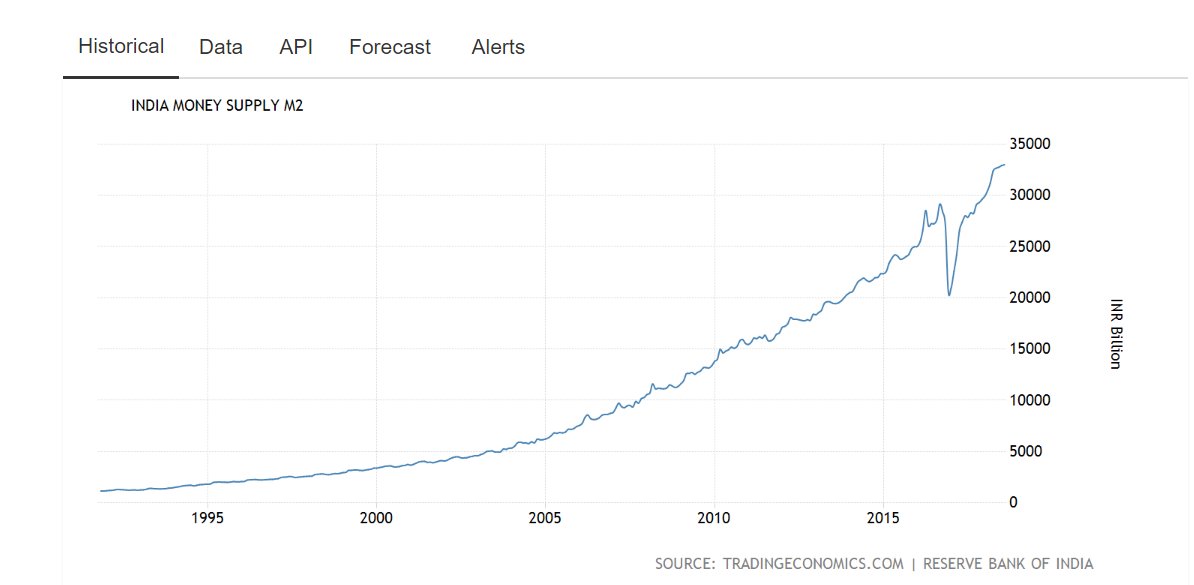

Additionally, printing more rupees is not going to solve the challenges.

The situation in India is not as desperate as in Turkey or Argentina, because FX reserves are not being depleted at high rate, but the trend is concerning and the outlook for growth, trade and fiscal balances is weakening.

The government has prefered to raise taxes and increase spending, and the demonetisation policy was a big mistake (read). All the cash that was taken out of the system came back a few months later. It is time for India to change its historical policies of subsidising the low productivity sectors to penalize the high productivity ones with more taxes.

India can easily navigate this turmoil if it changes some misguided demand-side policies. The question is, will the government do it? Or will they prefer to blame an external enemy and increase the imbalances?

If the government decides to ignore these issues, India could become the biggest risk in emerging markets and for the world economy.

Great analysis, it may be consequence of a world slowdown, i think the structural changes that you propose due to the indicators you point out are a good bet, not only for India but many other countries, personally I though that you could control bad indicators adjusting other indicators, but now i think that if policies are wrong no matter what you do any number could not ignore common sense.