This article was published in El Confidencial on September 8th 2012

“In central banking, as in diplomacy, style, conservative tailoring and an easy association with the affluent count greatly and results far much less” John Kenneth Galbraith

Euphoria. All is solved. After Thursday’s announcement from the ECB regarding unlimited purchases of short-term sovereign bonds, Draghi and Merkel, the “enemies of Spain and Europe,” according to some press, are now our saviours. Investors seek to protect themselves against inflation through stocks and commodities. By now there is no doubt that we are moving towards an inflationary period driven by financial repression and aggressive monetary policies.

From my point of view, the ECB plan only manipulates the price of short-term bonds artificially. Access to ECB funding is not linked to growth and solvency and is not aimed at rewarding the efficient. It will provide liquidity judging only by price without questioning whether such price is fair or not. It also runs the risk that countries receiving the liquidity will delay reforms knowing that if they push the limits they will receive a bailout. In essence, the ECB could be breaking the principle of responsible lending, a mistake that, in my view, is affecting the entire EU and discouraging long-term investment and capital.

I also believe that this plan simply transfers peripheral risk to countries like France, which do not have sufficient economic strength to endure the added risk. But above all, the ECB plan leaves the medium to long term solution of the economies in pro-state policies that do not promote the creation of new businesses and jobs. In the US I hear talks of SMEs, private job creation and growth, while in Europe it seems we only read about more government debt, to maintain subsidies and how to protect an unsustainable state apparatus, which acts as a crowding-out predator of credit to companies and families.

Questionable premise

The first mistake the ECB plan has, in my opinion, is to think that the bond yields of peripheral countries are “unfairly high”. It happened before with Greece and Portugal. It starts from the premise that bond yields are higher only because of the “fear of a euro breakup” when the reason is pure and simple of solvency. The problem would be much easier to solve if Spanish bonds were discounting an “imaginary” exit from the euro, but what we are seeing discounted is a much more problematic issue. Spain spends twice its revenues.

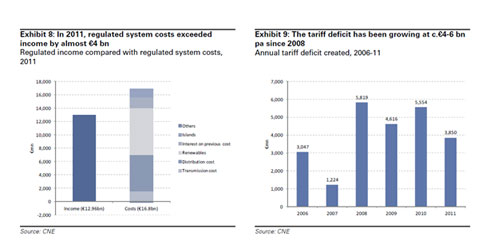

The negative surprises such as upward revisions in the deficit of Valencia by €3bn –a tiny 82% “mistake”-, the Catalonia bailout, the savings banks’ bailouts, a state deficit that has already reached 4.6% of GDP and that, including regions, may well be significantly ahead of the government target for 2012 … All these issues make the market discount that the gap between expenditure and revenues will expand further because costs do not go down. If the market believed that Spain runs the risk of leaving the euro, bond yields would stand well above 6% due to the inability of the country to finance the primary deficit outside the Eurozone.

The risk of perverse incentives

I see the 10-year bond at 5.6% and I fear that politicians will dust-off the cheque-book for more unneeded infrastructure and construction projects. Savings banks are denying credit of tens of thousands of small and medium enterprises –which generate 80% of added value and 70% of jobs in Spain- yet they seem more than willing to provide lending to high risk construction projects promoted by the regions and financed mostly with debt.

The most dangerous incentive generated by the ECB plan is that countries with greater difficulties will concentrate most of their debt in short-term bonds, which is the tranche that the ECB would buy, because they know that the long-term maturities will have very little institutional demand. The ECB expects that by doing so it will “force” investors to buy long dated debt. I believe the ECB is wrong. Think of the example of a company with poor fundamentals that sees one of its controlling shareholders buy more shares “to support the stock”. Investors do not follow this move except for the very short term. The monetary regulator assumes that credit investors “must buy” European debt and expects that by announcing “unlimited purchases” it will create a steady demand. In my opinion, this is incorrect as the underlying problems of the economies of peripheral countries are not even close to be solved, and will likely be postponed and dragged once bond yields are “perceived” low enough to “spend again”.

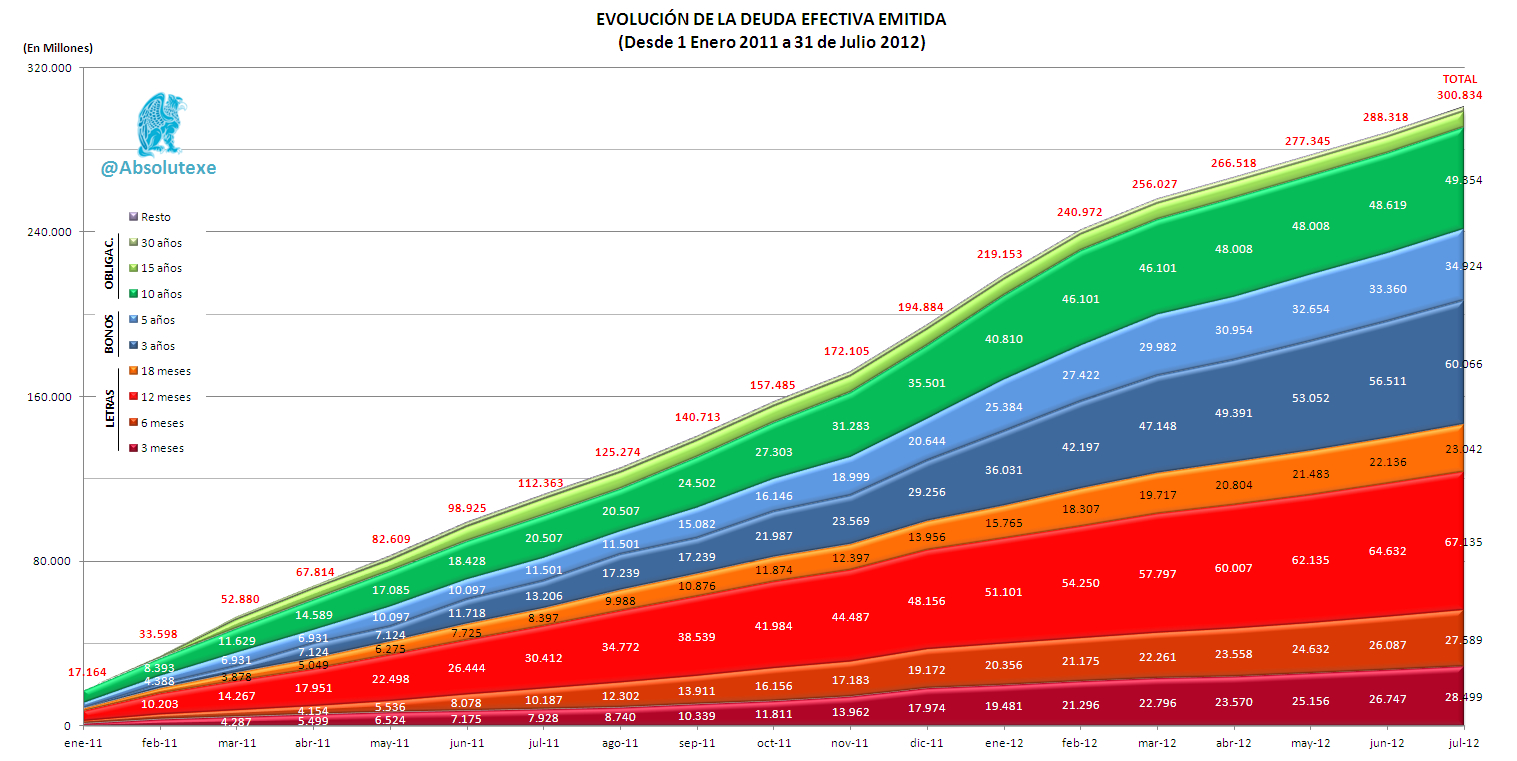

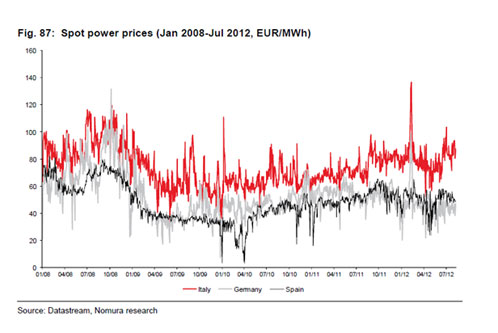

I am concerned about countries which are concentrating too much short-term debt, as the chart shows. The risk is multiplied because they are funding unproductive state spending and long term government investments with short-dated bonds, a dangerous recipe.

We must also note the danger of having “cheap” credit, which could lead many governments to delay cuts and, taking advantage of the complexity of the administration, take another spending party before the Troika comes and citizens see another round of tax increases.

The words that scare me: “unlimited capital”, “strict conditionality” and “sterilization”

The really sad part of the ‘rescue’ plan of the ECB is that not a single cent of that money goes to small and medium businesses, to create jobs. It goes to support a hypertrophied structure of the state, which will continue monopolizing the available credit under the promise that “something” will fall for the real economy … And it does not, because added to this ECB support countries face the urgent need to recapitalize banks, deleveraging. That is, less credit to households and businesses.Instead of supporting banks and government apparatus, and hoping that some crumbs will remain for the real economy, imagine what it would be if families and businesses were the recipients of this “unlimited capital”. Crisis over.Strict conditionality. The carrot and stick. Another problem is that the ECB plan makes countries very dependent on the ECB buying bonds to fund them while the European regulator threatens to withdraw such support if conditions are not met. The countries will be at the mercy of a quarterly ECB revision of its accounts and, therefore, subject to much greater volatility.

The strict conditionality also implies that budget cuts will be very severe. But because those cuts should be reflected in the accounts urgently to continue accessing the ECB line, governments might not focus on long-term structural reforms, focusing instead on elements of immediate impact. Tax increases.

Unlimited capital.

The ECB has not yet bought a single bond and euphoria takes over markets based on a word: “unlimited”.

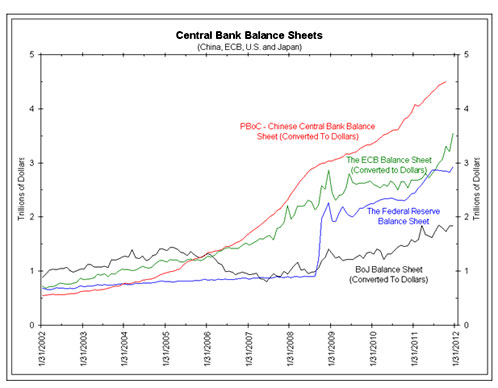

I’m surprised to hear those words as if they were logical. Unlimited capital. The Eurozone GDP fell by 0.4%, more than 2000 companies file for bankruptcy each quarter, unemployment keeps rising and Europe sees plummeting fiscal revenues. But we read “unlimited” without printing money. Unlimited means generosity with other people’s money. It means debt, and lots of it in a European Central Bank whose balance sheet in 2012 is close to 34% of Eurozone GDP, close to 3 trillion dollars, much more than the Fed (20%) and the Bank of England (21%) in their countries.

Sterilization means that for every bond it buys the ECB has to sell other assets to prevent inflation from rising out of control and to avoid borrowing massively. Sounds good? But so far Europe has proved unable to contain inflation, just disguise it, and the ECB debt has soared by 20% annually.The issue is that the central bank will be manipulating prices but will not increase liquidity in the system. Why do it then? It only impacts prices short term but the debt and liquidity crisis lingers.Another problem is called France, which would see bond yields soar just as it is growing debt and credit ratings will suffer, as Moody’s has warned. If added to this the ECB also sells French bonds, it will weaken another engine of Europe.From the point of view of institutional demand, foreign capital is likely to continue to avoid Europe as ECB intervention becomes a constant stream of “plugging holes” changing the price of assets and then, investors simply will not be able to invest in European debt on fears that prices are manipulated randomly and according to subjective criteria.

Reforms are not debatable

Every newspaper in Spain demands a bailout as if it was a donation and the end of budget cuts. It is neither. The ECB does not donate, it lends. Spain would not need a bailout if it managed expenses according to revenues, rather than waiting for the return of fiscal revenues of the housing bubble period to finance a hypertrophied state. And the consequences of a bailout are very relevant.

A bailout has a huge impact on the creditworthiness of Spain. And even if rating agencies will promise no downgrade to junk status, the market will do it, as it did with Portugal, Greece and Ireland. Spain has to assess this risk.

Minister De Guindos said Spain is carrying out the reforms that Germany undertook 10 years ago. Let us hope it is correct.

It is easy to reject reforms from Spain’s current perspective of a heavily subsidised nation with an “undeniable right” to debt, and claim that cuts don’t work. To illustrate why reforms are essential I would like to end with a few sentences of an article about Germany’s 2004 reforms, “The three crises that undermine the European colossus ” written by Jose Comas and published in El País in 2004, when many believed Spain was the rich champion of the world:

“Germany is riddled by corruption, recession and deteriorating public services. Its crisis is structural. Convinced of the need to renew a stagnant Germany, Schröder launched in March of last year the ‘Agenda 2010’ reform program. It was a plan to make cuts in social benefits rooted in post-war German culture, and to partly dismantle the achievements of social capitalism: reducing social benefits in retirement, health care, unemployment and making layoffs easier. Schröder opened the bottle and let go the spirits that will lead to political ruin”.

Schröder must be singing “I Hate to Say I Told You So” by The Hives.