Special contribution from Amit Tal:

Something disturbing is happening in the bond markets. It seems to me that the bubble that developed in the last 45 years is coming to an end. This process will likely lead to negative consequences in the form of fast inflation -in the best case- or hyperinflation -in the worst case-. In my opinion, central banks are clueless.

The beginning of the credit bubble happened between 1981 and 1982. We can identify this point in a number of markets: the stock market, bond markets and traded foreign exchange. This bubble has continued over the past 45 years and I really believe that most policy makers and economists know of no other way to manage the economy.

But first, I want to illustrate how the mechanism of credit bubbles works. I will do it with parallels between all economic agents and markets (government, companies, households) and the average citizen. For example, let’s say that a person is interested in taking a loan and when the time comes and he or she has to pay the bank, the person doesn’t have the financial possibility at the moment. The person faces two options: bankruptcy or a bigger loan on more favorable term (lower interest rate). In the past 45 years, all markets have prefered the second option.

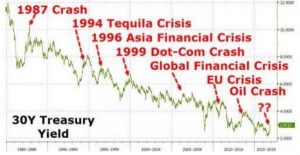

If we can understand this mechanism, we can understand this chart: 30y treasury yield. Any increase of interest rates (which could cause the mechanism of credit markets to stop working), caused a crisis in the market. Do these crises suddenly look better from a different perspective? They actually helped prevent the greatest crisis of them all – the explosion of the credit bubble.

Is there a chance that central banks know this and try to do everything in their hands to prevent this explosion? A looki at the bond market proves so.

For me, it looks like the market must have crises to prevent a very high rise in interest rates that would cause an explosion of the big bubble. Have central banks created these crises in recent years: the answer is YES.

So what has changed now?

I think this time it will end differently. Mostly due to the actions of central banks in the last 8 years. Once inflation started to build in the United States, the Federal Reserve wanted to raise interest rates. However, this action will no longer work, and brings more inflation.

How It Works?

US raises interest rates. Money out of other countries (Japan, China, Eurozone) escapes, interest rates of those countries rise, and central banks inject even more money to their bond markets to prevent the explosion of the big bubble. This creates even more inflation. This would require the United States to raise interest rates again. This is a circle that feeds itself. Using interest rates no longer works. I don’t think the Federal Reserve understands this and probably will raise rates in March.

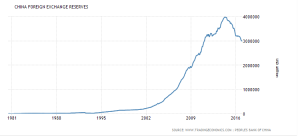

Let’s take China as example. US moves cause it to burn its foreign exchange reserves. The Chinese understand their currency is going to hell, and start to buy any property, creating wild inflation, which requires the United States to raise interest rates again. And it repeats itself.

Fast inflation. Just the beginning. China CPI

This circle is happening in all countries .

This circle is happening in all countries .

So is there an alternative?

If the central banks leave the bond market alone, it will complement the shortfall. In other words, lead the way to an explosion of the credit market. 2008 would be a holiday trip compared to what will happen in this case. I do not think this option is realistic, so the bubble will be fed.

So how to trade in the current situation?

When there is an inflationary situation, the last thing you want is to be out of the market.

It means: Long aggressively on indices (which have risen a lot already, but it’s nothing). But keep an eye on the debt crisis. The US dollar will be the king in this situation.

Finally, I would like to share two graphs that help to show the break deviation in the bond market.

The first chart is 5y treasury yield over ץthe past 45 years. We can say it is breaking a pattern of 45 years. This is just the start.

The next chart is DXY. Breaking a pattern of 45 year

Conclusions

I think that the markets have opened the Pandora’s Box. The result can be hyperinflation (if central banks launch new programs), followed by the collapse of the largest bubble in history.

Or we are already heading for an explosion of the biggest bubble in history.

A Special contribution from Amit Tal “The Big Shorts trade”

@amital13