“I got a plan. Run away fast as you can “Kanye West

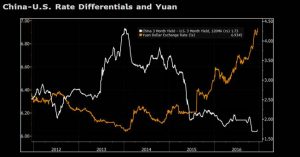

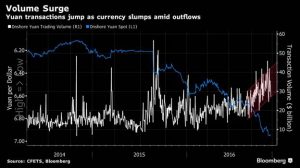

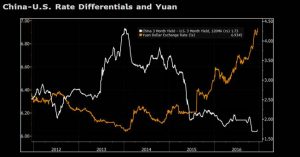

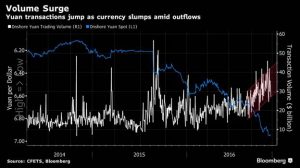

China’s capital outflows have increased 51% since the first months of the year, averaging $ 43 billion in December. In the last twelve months the figure, according to Goldman Sachs, exceeds one trillion, and Natixis estimates the number for 2016 at 900 billion dollars.

China is once again the great challenge for world growth in 2017 and the decisions of the Chinese economic agents themselves show the risk of a huge devaluation, higher than estimated, and an economy that has added more debt so far this year than the US, EU and Japan combined.

The Chinese bubble is exploding in slow motion and it is normal for Chinese companies and savers to expatriate capital – either via acquisitions or directly with deposits – as there is increased likelihood that the Chinese government will decide to solve the huge imbalances of the Chinese economy via financial repression.

The defenders of the wrong Chinese model always come to two fallacious messages. GDP growth and the country’s huge foreign exchange reserves.

A country that needs four times more debt per unit of GDP growth than eight years ago is clearly unsustainable. And China has already abandoned its “target” to grow by 6.5% in 2017.

By 2016 China’s debt already exceeds 250% of GDP, led by semi-state companies – which count as “private debt” – and the housing bubble. China already spends a third of its GDP on interest payments.

The other reason some use to justify the Chinese imbalances is the huge amount of savings and assets of the Chinese economy. Savings including deposits of 205% of GDP and assets held by Chinese corporations equivalent to 550% of GDP. This argument will sound familiar to the Spaniards, because it was repeated again and again during the bubble of 2007. “The debt of companies and families is not worrisome because it is supported by assets that can be sold to reduce debt “.

There are only three problems.

- The price paid by these companies for the assets has been absolutely disproportionate with their current value, making acquisitions at inconceivable multiples that today would entail enormous write-downs.

- Second, the vast majority of the assets of the semi-state enterprises – responsible for much of the increase in indebtedness – are simply unsaleable in the face of a Chinese slowdown and unstoppable devaluation.

- And third, the debts associated with the real estate bubble becomes unpayable when the asset falls, because the ability to sell these properties is very low.

When some say that the vast majority of outflows of capital are for acquisitions and, therefore, it is a good move, another reality is disguised. Many companies will make any acquisition at any price and in any sector to reduce exposure to the Chinese bubble.

The China housing bubble was encouraged directly by the authorities. In 2014 the Chinese Central Bank massively reduced restrictions on credit and interest rates. At the same time, the Securities Regulator removed restrictions on real estate developers to raise capital and sell bonds and stocks, sending the market to price increases of 20% a year.

The answer was immediate. In October 2016, the 196 Chinese listed real estate developers more than doubled their debt, from 1.3 trillion Yuan in 2013 to around 3.3 trillion Yuan. Household debt soared from 31% to 41.5% of GDP. Anyone can see that falling prices and a domino bankruptcies would have a huge impact on secondary markets and large cities. It would be virtually impossible to control the impact.

That said, Chinese debt is mainly denominated in local currency and held in local banks, which leads us to think that the contagion effect to the rest of the world could be low, financially, but not in terms of growth and inflation expectations.

That the Yuan has depreciated against the dollar so much and Chinese exports have fallen shows another of the great problems of the Chinese economy, its low competitiveness and poor added value.

China’s problem is no longer debatable. The brutal increase in debt in 2016 coincides with a strong dollar and a US administration aimed at breaking the huge trade benefit that China has with the US.

If China does not do something really drastic to stop the debt orgy, the problem will be bigger in the medium term. The big dilemma is that the Chinese government seems not only unable to control the debt of semi-state enterprises, but is actually encouraging it via lower interest rates and softer conditions, and that taking measures to stop the housing bubble inevitably leads to a contagion effect. But it clear now that mild measures will not work.

Like all bubbles, which are always generated in assets that are widely considered safe or very low risk. China’s one has been created under the religious belief that the government can control everything because it is an intervened economy. The Chinese risk is not reduced because it has not ‘exploded’ in 2015 or 2016, it is increasing.

. “

. “

“Let me tell you a story to chill the bones About a thing That I saw ” Janick Gers Steve Harris

“Let me tell you a story to chill the bones About a thing That I saw ” Janick Gers Steve Harris