(This article was published in Cotizalia on May 26th, 2012)Another week and as part of our leaders think that the rest of the world is wrong, capital continues to fly away from Europe. €700m a day according to press. The credit and financial credibility of the Eurozone couldn’t be any lower. Yes, my friends, investors will not return if the numbers are not solid, and politicians cannot prohibit selling.

Eighteen European summits in two years. European politicians seem increasingly more detached from the real problems of the economy. How can they meet again without reaching an agreement on anything? They seem to give a message of selfishness to the public, and that they are cheating to investors.

We get constant calls to promote growth, which would be fine if they were not calls to encourage the same subsidized wasteful spending of the past. Funily enough, if the EU had cut part of its €141bn budget, out of which 45% goes to “employment and growth”, by today the continent would have a lot less debt and a lot more growth. In any case, I think that we will gradually see a more logical reform agenda for Europe.

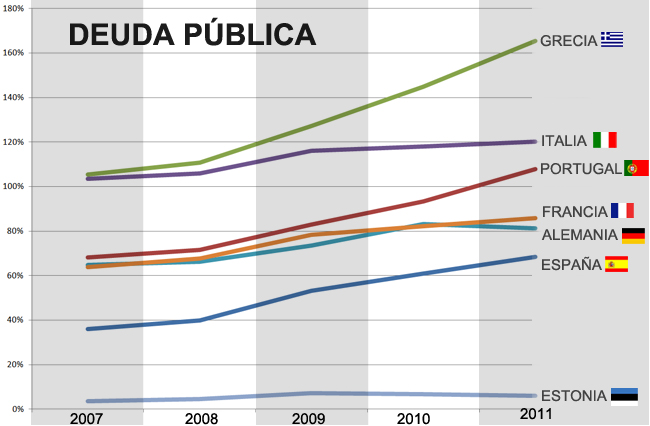

We are outraged to see that Germany finances itself at near zero rates while Southern Europe countries finance themselves at 6% or higher. But instead of thinking that, perhaps, the Central European austerity plans work, the press and politicians say that Germany is going against us, “drowning” us.

We hear that the blame for the debt crisis should be pinned on Germany which broke the deficit limits in the early 2000s, which “obviously” led everyone else to go into a debt frenzy. Here nobody is to blame for anything. It’s like those people that stuff themselves with Big Macs and blame McDonald’s for their obesity. If a bank fails, blame it on the “ill will of the anglosaxon press.” If the stock market falls, blame it on Greece or hedge funds, or both. And the giant real estate bubble, the massive subsidy culture and the savings banks’ recklessness have Helmut Kohl to blame. Please

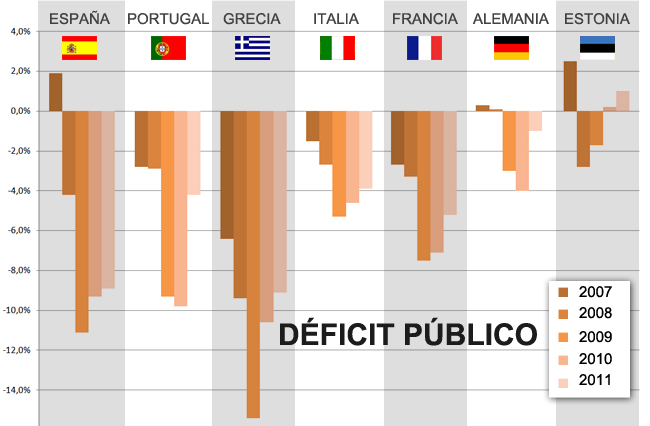

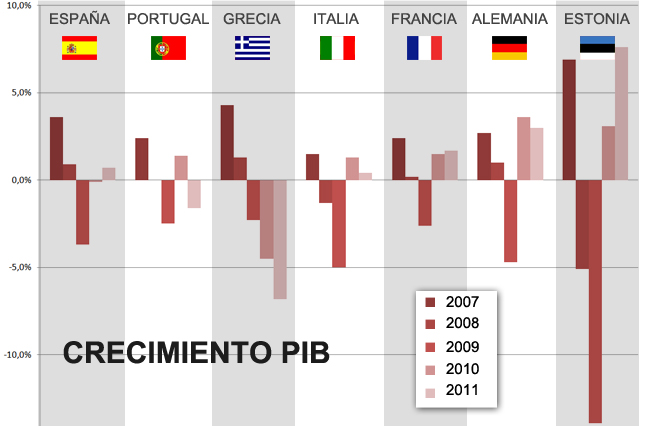

However, countries that have implemented austerity and budget control, from Estonia to Germany, are those who are better off today. We should not demonize them, but learn together how to attract capital and get out of this debt mess. Austerity -cutting giant political spending- and growth -not subsidies.

Austerity and growth are not mutually exclusive. Reckless spend and growth are.

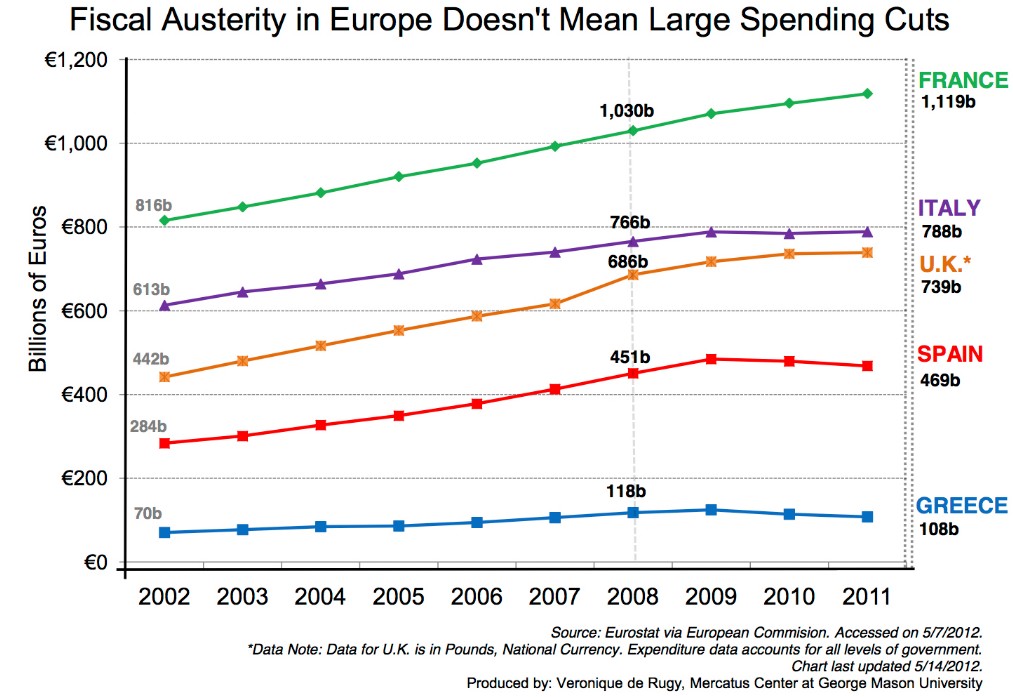

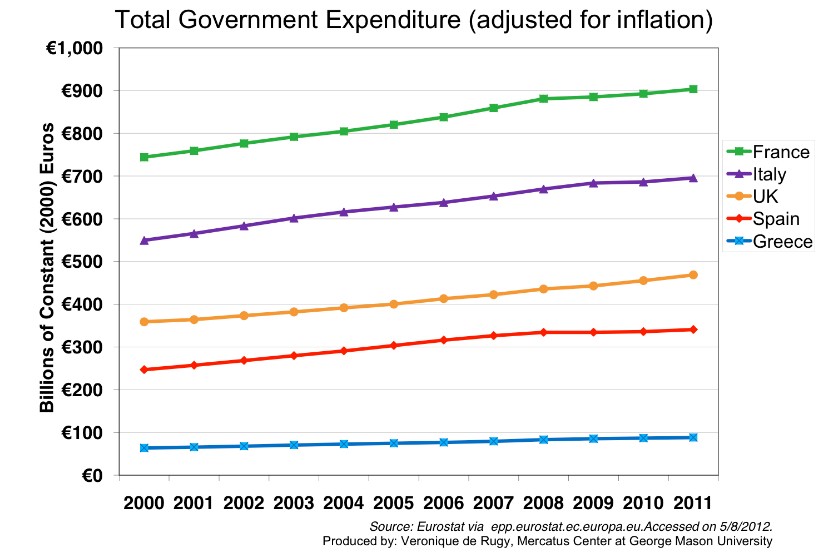

From a market perspective, the only way to reduce risk premiums and attract investor interest is just moving towards a single tax system, and to contain government expenditure, which has done nothing but grow even in years of “austerity”. Public spending in the EU has not fallen in most countries between 2008 and 2011. In Spain it is still 4% higher than in 2008.

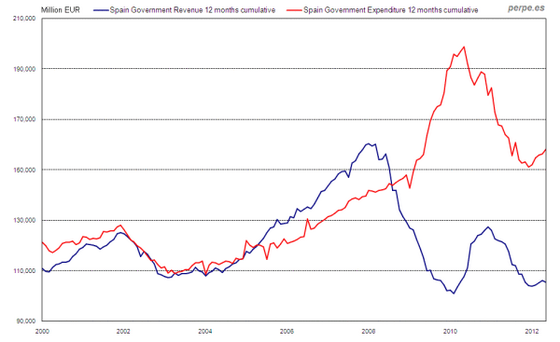

The graph below is devastating. Either we adapt spending to “pre-bubble” levels or the CDS will not stop rising.

Why we should not allow the ECB to become the worst hedge fund in the world

When we say that countries should receive more money from the European Central Bank we forget that it can not infect its balance sheet at the rate of one trillion euros per semester.

Germany, the Netherlands and the countries of central Europe are those who have to carry the financing risk. Not France, which has a serious debt problem. And if they close the tap, it will be bad. But if they open the tap too soon and too much it will be worse. Because they run out of water for the next fire.

There are several things we should know about the European Central Bank:

- . The ECB’s current debt is monstrous. At 23 or 24 times its assets, with only 82 billion euros in capital and reserves. Of course, the Fed’s balance sheet is also unacceptably high, 53 times its assets … The big difference is that the capitalization of the Fed does not depend on severely indebted entities such as the European states. But as I always say, we should not copy the ones who do wrong and reclaim our right to do worse. Let’s remember that the U.S. is on the brink of a “fiscal cliff.”

- . The ECB weakens with the losses incurred from its purchases of sovereign debt. We are talking about latent losses between 55 and 70 billion euros (source Barcap and Open Europe). Of course, many will say that there are no “losses” because the ECB has not sold the bonds -a “bull market” argument- but anyway we want to see it, systemic risk is increasing and does not dissipate by buying more bonds, as we have seen since November. In fact, losses have increased in 2012.

- . The European Central Bank has already contributed to the stabilization of the European market, excessively aggressive and quickly. With more than 1 trillion. And the ECB should keep powder dry in case of future emergencies, because the future ain’t what it used to be, to quote Jim Steinman.

- . Saying that “we must use the money of the ECB” is false because it is not disposable money. It is debt, which must be funded through more sovereign debt. The ECB Balance sheet growth goes also against our future tax bills.

- . To those parties that demand that Europe should “capitalize “the debt of the ECB: Where will that money come from? Furthermore, it an indirect default that would severely impact the creditworthiness of all solid countries of the Eurozone.

However, I keep hearing that we need a growth plan, which sounds great if it was not for the fact that it’s a borrowing plan. As of today, and after two years writing about it, I can not believe that Europe is betting on more debt. Remember that almost no European country has created GDP growth ex-debt in the last 22 years. Have we not learned from all those ridiculous infrastructure plans?. I leave you a figure: the European economy generated less than $1 of GDP for every $ 2.5 of debt (Barcap and IMF data). That is, we continue to build the huge ball of debt in the vague hope that growth will multiply exponentially some day.

This week I have seen some possible proposals that would go to the June summit. The recapitalization plan in Europe would happen of three phases:

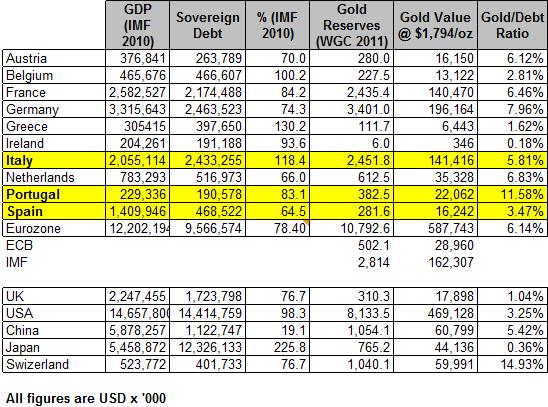

1) A fund to pay debt (Redemption Fund) that incorporates the indebtedness of over 60% of GDP backed by gold reserves of the States. This fund would repay that debt against a commitment to economic reforms, adjustments and more severe cuts guaranteed in the Constitutions of the member states. The problem? The gold to debt ratio of troubled countries is very low. An average of 6.1% for the Eurozone and 3.5% for Spain or 5.8% for Italy.

2) A line of credit to banks to ensure liquidity needs, but not capital needs. We seem to forget that these are mostly all listed companies that can and should access their investor bases to recapitalize themselves.

Additionally, the idea is to try not to create false inflation . The economic miracle of Central Europe is based, among other things, on multiplying by three the number of low-paying contracts (mini-jobs). An increase in inflation would be lethal because the euro-zone countries have never been able to control it when it overshoots, especially when it’s external inflation (commodities).

And finally, tackle the unjustified strength of the Euro currency versus the US dollar, to devalue and promote competitiveness, reducing the need for internal devaluation we have seen so far. It will take the market to do this last bit, as economic expectations of the euro-zone are adjusted to more realistic figures.The key is shows in the above graph. Either we attract private capital back once we have proven real creditworthiness, or we continue whinging blaming the Germans, the markets or Hedge Funds.

Hopefully in June, EU leaders will forget about trying to re-create 2007 and think of a more rational future.To watch my interview on Al Jazeera about the Bankia and Spain (Realplayer Quicktime or Oplayer needed): http://dl.dropbox.com/u/62659029/iv_daniel_lacalle_250512_0.mpg

Eurobonds? No Thanks. Debt Isn’t Solved With More Debt: http://energyandmoney.blogspot.co.uk/2011/11/eurobonds-no-thanks-debt-isnt-solved.html#

What happened to put Spain on the verge of intervention?: http://energyandmoney.blogspot.co.uk/2012/04/what-happened-to-put-spain-on-verge-of.html

Why Italian and Spanish CDS can rise 40%… and Greece is not to blame:

Rescuing Greece does not solve anything in a country that overspends 8% of its entire GDP every year, while revenues collapse and new expenditures appear every quarter. A bottomless pit in a system, the euro, within which it can not and will not recover.

Rescuing Greece does not solve anything in a country that overspends 8% of its entire GDP every year, while revenues collapse and new expenditures appear every quarter. A bottomless pit in a system, the euro, within which it can not and will not recover.