(This article was published in Spanish in Cotizalia on October 7th 2010)

The Repsol sale of 40% of its assets in Brazil to China’s Sinopec has generated some controversy in the media all week. And in several cases we have seen the term “bubble” used for the transaction.

China has a very clear objective, which is to secure its energy future and build up reserves in new frontiers, from Uganda and Nigeria to Iraq and Latin America. The war for natural resources. In 2009 and 2010 YTD, China has acquired over US$115bn in international oil and gas assets. And while some companies and the analyst community are surprised by the prices paid, we still see the shopping spree accelerating.

Sinopec has paid $7.1 billion for 40% of Repsol Brazil. This implies a “headline” price of about $ 15/barrel for the reserves, and the market compared this to the price of $5/barrel estimated for the value of the Brazilian assets in January and with the $8.50 per barrel paid by Petrobras to the Brazilian State for their new wells last month. “Bubble?” Let’s figure by figure.

For starters, the media has ignored the fact that Sinopec retains a 40% interest in the cash injected in to the IPO. So the net transfer to Repsol is 60% of USD7.1bn in return for 40% of contingent reserves of 1.2bn. So $4.3bn for 480mb or USD9/bbloe (or USD7.1/bbloe including the net risked exploration resources).An excellent figure for Repsol in any case .

Additionally, we should not confuse the value of assets within an integrated industrial group (the $ 5/barrel above) with its selling price if they are disaggregated. All oil majors are trading at a huge discount on their sum-of-the parts of its assets. For example, BP has sold $7 billion of assets to Apache at an average of $7.8/barrel. This does not mean that these assets should be valued within the BP group at these multiples. It is the historic conglomerate discount of 30-40% of all the mega-cap integrated oils.

Also we should not confuse the value that the Brazilian state uses to transfer assets to their flagship company, Petrobras, the $ 8.5/barrel, with a private transaction.

The Sinopec deal is justified from the perspective of other similar transactions made by Chinese enterprises and state-owned companies with a long term vision. Sinochem, China, paid Statoil $15/barrel for their Pelegrino assets in deep water Brazil in May, Sinopec itself paid $16/barrel for Addax, high risk assets in Nigeria, and KNOC, Korea, has paid $12.5/boe for Dana Petroleum, with much higher gas content, which is obviously less valuable than oil.

On the other hand, Chinese companies start with a much lower cost of capital assumption than their American or European competitors. The Asian giants do not have to worry about their debt, and, of course, have no need to pay enormous dividends like the integrated oils, that neither has served them to generate share price appreciation or to better compete in the M&A arena. China has plenty of capital and lacks natural resources to ensure its long-term supply.

Is this a bubble? No. It is simply a different use of capital and a longer term horizon. And it is not, moreover, for three reasons:

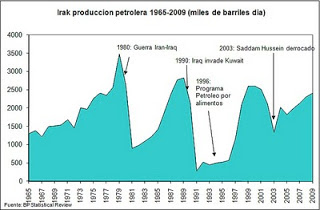

a) Oil assets are very scarce. To have a bubble we would have to see a risk that these assets were multiplied or fall dramatically in value, but, as stated in this column, we must take into account the scarcity value and the undeniable truth of the gradual decline rates of the oil reserves. Proof of this is the race that has been generated to participate in the 11 licenses for Iraq, where the companies (including China) will invest up to $200 billion in the next ten years accepting returns not exceeding 12%, and with an enormous political risk.

b) Unless we believe the demand for oil from emerging nations will collapse, the cost of access to natural resources is irrelevant compared to the risk of losing supplies or lose competitiveness. Oil reserves, therefore, should be seen as a cog in the huge Chinese machine. Oil is an “input”, and the relative price of these reserves does not make the total cost of “China Inc.” less competitive when the variables are planned in detail.

c) State-owned enterprises plan their projects with oil price assumptions that are higher than those used by the integrated oil sector, which is still planning at $40-50/barrel. Therefore, these companies are more than happy to have access to returns of 12-16% at $ 80/barrel.

As a friend of mine reminds me, China has a problem of too much cash, their US dollar stockpile is a perishable asset, and they can see value in oil assets above what assets are worth to others not only because they use a higher oil price, but because in any planning they use a sizeable revaluation of the Rmb.

In summary, while the European Union continue to waste time with pointless debates, instead of securing oil and gas reserves and diversify our access to natural resources, the rest are winning the war for natural resources. We’ll see if this is a bubble. I doubt it.