This article was published in El Confidencial on Sept 29th 2012

“Deficits mean future tax increases, and politicians who create deficits are tax hikers”, Ron Paul

Spanish 10 year bond yields remain stubbornly at 5.85% while spreads widened to 450 basis points after the announcement of a budget that provides more questions than answers.This week El Confidencial published that the Spanish Government restated the 2011 budget deficit from 8.6% to 9.44% and 2012 could slip to 7.4% from the current 6.3% target. We talk constantly of regaining market confidence, but such confidence is not going to come with constant budget revisions. It will be achieved with better than expected numbers. This is the reason why I am concerned about optimistic assumptions in the budget and aggressive tax increases added to generosity in maintaining a bloated state. I mentioned a few months ago that Spain needs to apply the red pencil throughout a bloated state that spends, even in alleged “austerity times” the same funds as in the peak of the housing bubble (see here).

The 2013 Budget is a step, but an insufficient one

Spain’s Economy Minister, Mr Montoro, said that “it is impossible that Spain has lost 70 billion euro in revenues only due to the crisis.” With the number of companies in business falling from 155,000 to 135,000, the real estate bubble bursting from 650,000 homes built per year to 150,000, the collapse of the industrial activity of 2% per annum and the rise in unemployment to 24%, I think it is admirable that revenues have only fallen by 70 bn euro.

While economic measures focus in recovering lost revenues of the housing bubble that will not return, the investor perceives that Spain could forget about the medium-term risks of a predatory fiscal policy.

Voracity in tax collection with possible impact in the medium term

Almost half of the budget adjustment is, again, tax increases that reduce consumption,weaken the economy and prevent companies from creating jobs.

In a recent analysis, JP Morgan warned about a few key aspects: loss of deposits, industrial decline, poor profit margins and stagflation. The loss of deposits is less than what is estimated in the press, announcing almost 120 billion, but we should never underestimate 30 billion as “irrelevant”.

However, in Spain between 1500-2000 companies file for bankruptcy each quarter. In addition, the CPI soars to 3.5% when GDP decreases 1%. This risk of “stagflation” -inflation with recession- can be very dangerous for the economy. All this happens in an environment where profit margins have decreased to make many of the large companies and SMEs generate margins below cost of capital. The economy remains extremely rigid and tax increases are reflected in the prices immediately. Adding an unemployment rate of 24% to the equation creates a difficult horizon for recovery.

While the general government deficit remains a concern, we must also highlight the positive , and in July there was a current account surplus of 500 million euro. This is important because, if confirmed as sustainable, it implies that Spain reduces its external financial dependence .

We must appreciate it, but we must not forget that it is, in part, the result of the inability to continue to import due to falling industrial demand. Spain is still not competitive and structural reforms must stem the drain on companies, rigidity and erosion of profit margins inflicted by aggressive tax increases.

If companies are not created, if SMEs do not generate profits, then banks do not finance, debt increases, tax revenues collapse … and deteriorated companies do not hire…and the unemployed do not consume.

If we prevent businesses and citizens from becoming richer, we impoverish the country

Goldman Sachs called the 2013 budget “Running to Stand Still” referring to the U2 song about drug addiction. The market is concerned about optimistic tax revenue expectations (+4.4%) and estimates of increase in social security contributions that are inconsistent with the government’s own estimates of unemployment increase. The market sees a high risk of seeing expenses rise above estimates and revenues fall short of target.

For example, sensitivity to two items is enormous. If VAT revenues do not increase by 13%, as budgeted, and they will very likely not increase due to loss of consumption, then the government’s estimates of tax revenue growth would fall to almost zero.

If transfers to regional governments continue in 2013, something which is quite likely given the regions’ troubled situation, that means another 12 to 16 billion of additional spending.

In terms of budget targets, it appears that the government has fallen into the same trap of previous governments. To provide estimates of GDP growth (-0.5%) that few analysts consider as conservative. The consensus range for 2013 is between -1.2% and -2%. Should the government not have taken the opportunity to build trust giving estimates in line with the consensus of economists and then beat expectations? Beating estimates is essential to regain market confidence.

The goal should be maximum expenditure, not “deficit as a percentage of GDP”

To avoid suspicions on revenue estimates, the state should give a maximum target of spending and put up remedial measures every time such goal was surpassed. If the target is “deficit to GDP”, it masks poor budget execution with ratios that can be manipulated.

Austerity? Where?

What I think is most important to note is that these budgets, as those of 2012, cannot be described as austere. Public spending rises by 5.6%. Yet I hear over and over that the problem is “the cost of debt” … as if the cost of debt was an alien who came down in a UFO surprising the population. As if such cost of debt is not the result of massive public spending.

But even if we deduct the cost of debt, primary expenditure falls only by 0.6%. This is before the regional communities publish their expenses and before any deviation due to bank bailouts or “unexpected” one-offs.

This is not austerity, it is, at best, a slight budgetary restraint

I do not know of any family that comments about their budget “we are doing okay if we remove the cost of the mortgage.” The Spanish budget does not show real cuts, just very slight revisions of previous years’ overspending.

We should highlight it because there is a huge difference between austerity and “less overspend”. Spain will keep spending, including all administrations, almost 20% more than it earns, and will also spend more than it earns without the cost of debt, leading to having to borrow around 200bn a year.

The difference between the “red pencil” and the “Troika axe”

As Art Laffer said, “give me a red pencil and the budget and I will reduce the deficit to zero in a week”. The reduction of debt, not the deficit, is the only solution. And that will come only from cutting spending. Or the Troika will do it for us, but they will do it unfairly and badly.

It is important to repeat that the State and the regions should reduce absolute expenses much more severely, that the state cannot be 56% of the economy, including all public enterprises and that Spain cannot spend 20-25% more than it collects as revenues.

There must be serious cuts in political spending. The presidents of regional governments or ministers cannot have more counsellors-each-than David Cameron.

The Spanish fiscal consolidation process will not be credible unless it structurally reduces the largest expenditure items.

The red pencil. The State can immediately attack four items:

- Public salaries , a spending of over 100 billion. We have higher public wage expense per GDP than the EU average but a number of civil servants per citizen that is less than the EU average (Eurostat). What is the problem? Too many bosses and too little workers.

- Consultants and duplicated administrations, which, according to the Association of Businessmen and the PP when it was in opposition, cost more than 22 billion euros. Even if it was half it would be too much.

- Unproductive investments : In the central government budget of 2012, direct investment in infrastructure- useless high speed trains, ghost “culture and arts” cities and others- amount to 11 billion. According to the latest Stability Program, the gross fixed capital formation, which includes more than infrastructure, was 2.8% of GDP in 2011, and another 1.0 to 1.2% is expected in 2012 and 2013.

- Subsidies: The amount in 2011 was 11.3 billion and, even in 2012 and 2013, subsidies are expected to exceed 0.8% of GDP. If we add transfers and ministries, we easily reach 15 billion.

Of course, dozens of public television networks, hundreds of public radios… If we attack subsidies and administrative duplication Spain can avoid the “axe” that will come with the bailout, which will look at the expenditure items of over 30 billion and sever them, no matter who is affected and how. Those who call for an immediate bailout request tend to forget what comes with it:

- Pensions, a cost of over 100 billion. They may have very significant cuts.

- Unemployment benefits, which generate a cost of c30 billion.

- Dismissal of civil servants. Not pay cuts, dismissals.

The impact on companies

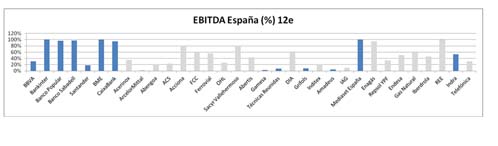

The Spanish budget impact on companies is not irrelevant. In a very interesting analysis, Ahorro Corporacion shows the companies that are most exposed to Spain (in blue) and exposed to civil works, capital-intensive activities (in gray).

The impact of the Budget, if we assume that the fall in GDP is only 1%, ranges between 5 and 7% of net profits. Less revenue from income tax, less growth, fewer jobs.

These budgets should have aimed at reducing Spain bond yields. They didn’t.

We know that the country risk will not be reduced if revenue estimates are revised down, spending items are revised up, and debt accumulates with a state structure that survives with short term emergency loans from the ECB without any control of how and when they are granted. Spain runs the risk that the system is not only tax-ridden and confiscatory, but insolvent … and investors, financial or industrial, might think that such risk is too high to invest.

From Bloomberg:

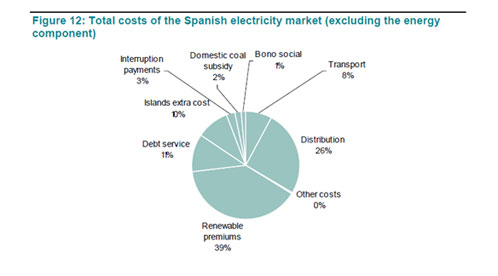

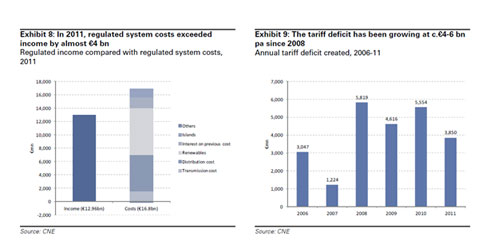

As per the Ministry’s budget statement, Spain plans to borrow €207.2bn next year. Budget Minister Cristobal Montoro said Spain’s debt will widen to 90.5% of GDP in 2013 as the state absorbs the cost of bailing out its banks, the power system, and euro-region partners Greece, Ireland, and Portugal. He added Spain’s budget deficit target of 6.3% will be met because it can exclude the cost of the bank rescue. This year’s budget deficit will be 7.4% of economic output.

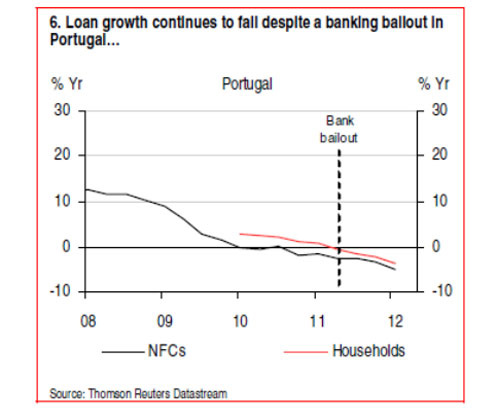

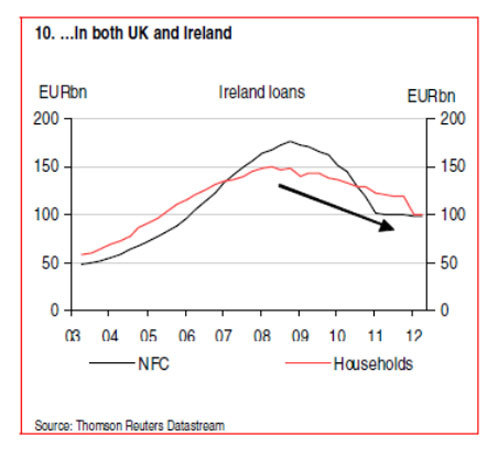

But once the bailout was in place, ten-year bonds just kept rising and the rating agencies downgraded the three countries to junk status. None of the countri

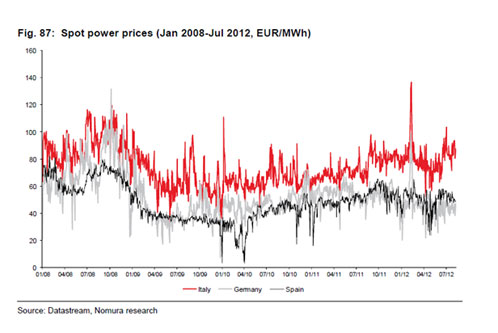

But once the bailout was in place, ten-year bonds just kept rising and the rating agencies downgraded the three countries to junk status. None of the countri What has been the benefit so far of the massive purchases of Portuguese, Spanish, Italian and Greek bonds than loading the ECB with losses of 56 billion?, Nothing else but making the ECB the most indebted central bank … and no positive effect either on bond yields or the economy of the countries. “Watering the wine” to make it appear that there is more quantity in the barrel.

What has been the benefit so far of the massive purchases of Portuguese, Spanish, Italian and Greek bonds than loading the ECB with losses of 56 billion?, Nothing else but making the ECB the most indebted central bank … and no positive effect either on bond yields or the economy of the countries. “Watering the wine” to make it appear that there is more quantity in the barrel.