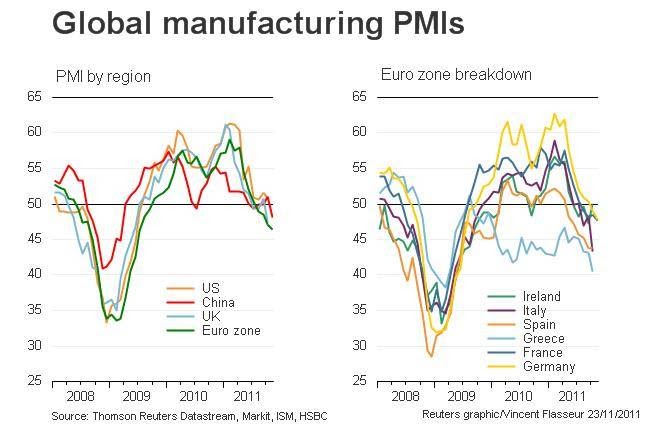

(Published in Cotizalia on Nov 26th 2011)The image of Merkel as an evil monster because she rejects Eurobonds increases by the hour.The collapse ofthe Eurostoxx and the markets in general, shows why. Investors have positioned themselves long in risky assets waiting for a rally that is not justified by fundamentals, after the poor results of the third quarter, or by macroeconomic expectations, with three banks slashing global GDP estimates again.

In this environment, why are 65% of investors overweight in European equities in their portfolios? Easy. Waiting for a shot of adrenalin, a glass of whisky to the alcoholic, a new vial of crack to the addict. We demand more debt, Eurobonds, or a massive stimulus plan, now. And who are the strongest supporters of these Eurobonds, demanding that the ECB infects its balance sheet with more peripheral euro-debt and to expand the EFSF, the stabilization fund? Surprise, the French, Italian, Spanish banks and so on. Entities”so cheap” that only have an average of 25 times debt to assets, and need €250 billion to stay afloat in the “running to stand still” race of exponential debt.

Why are Eurobonds a bad idea?

Imagine if all the companies in the Ibex 35 or the CAC or the Mibtel, with different managers, different businesses and different balance sheets, decided to issue a common bond to meet their refinancing needs. The interventionists and their media messengers would tell you that it is a great idea because the most indebted companies would benefit from the credit rating of the strongest, right? Well, no. It is the opposite.

We learned nothing from 2008, the sub-prime mortgage crisis, the mega mergers of savings banks or the tech bubble. Risk is not dissipated by accumulation, it spreads and it is contagious.

Those who are rubbing their hands waiting for a transfer of wealth from Germany and Central Europe to the peripheral countries of €134 billion euro (the difference in cost of financing if we use the average spread between the bonds) do not realize that the transfer would be the reverse. Negative for all.

In the same way that a solid and attractive stock collapses if the company acquires a poor quality asset even if it is “small”, the implied yield of Eurobonds would rise between 35% and 40% compared to the current underlying asset (the German bund). Furthermore, the risk premium of these Eurobonds would increase to match most of the default risk of the weaker economies.

The Eurobond not only does not protect in bad times, but in times of economic prosperity it does not allow emerging economies to benefit. Are we confident that when Spain or Greece or Portugal recover, Italy or Ireland are going to follow? And do these see a benefit of merging growth prospects with Greece or Spain risk? Imagine if the United States and Mexico launched a joint bond. In a recession, the bond would discount a very significant Mexican risk, and in economic growth times, it would discount part of the relative unattractiveness of a mature country.

I wonder why in Spain the local politicians feel so happy to accept the perspective of a Eurobond, when they know and can quantify the risk and opportunity that the Latin American crisis gave, which today saves the balance sheet, growth, and risk premium of Spanish companies.

It’s even worse. If one country accepts the Eurobond and the economy starts to take off, as it happened in Spain between 1990 and 2005, the cost of funding will be negatively impacted by the economies that now seem very solid and that weigh in times of growth. Do we forget when Germany and France were in technical recession and peripherals grew 3% pa?From the standpoint of the stock market and the refinancing of corporates, Eurobonds are extremely negative. European companies have 1.1 trillion euro to refinance between 2012 and 2013. Most of them have a much lower risk premium compared to their home countries, thanks to a policy of internationalization, debt reduction, cost saving and active management of cash flows. Well, a Eurobond would not only mean an increase in sovereign risk of the underlying higher quality asset (German risk in this case), but the cost of refinancing of companies would also rise proportionally all over Europe, regardless of the country, losing all the advantages of the policy of corporate austerity applied since 2007.

In addition, the route to Eurobonds, perfectly planned from Brussels, is a route that uses the years 2012 and 2013, in which the peripheral countries have more debt maturities, to curtail economic sovereignty in favour of three entities, the IMF, the ECB and the EU, which have shown no ability or track-record of doing things better than the disastrous individual governments . Changing a bad manager for three bad ones is not only to lose sovereignty, but to become an “experimental” economic province. From Islamabad to Islamaworse.Eurobonds would be the ” big short ” of 2012

Read Michael Lewis’s book “The Big Short”. Packaging and disguising risky assets into a conglomerate sold artificially as low-risk is creating an enormous short opportunity. Specially when they would “rate” them as Top Quality probably on their own, as Europe doesn’t want “foreign” rating agencies meddling in its pretend-and-extend scheme. Nothing better than over-priced over-valued assets with huge hidden risk to put some shorts of spectacular magnitude. I assure you that if Eurobonds were approved I would try to launch a Short Only fund the next day. Oh, and if the interventionists ban shorts, there will be a stampede of capital outflow out of Europe again. And goodbye Eurostoxx.

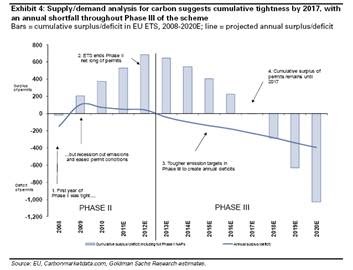

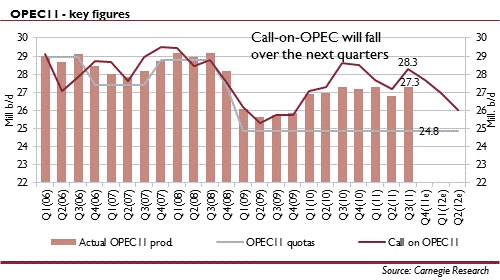

Let me give an example, courtesy of the great John Hussman. Almost all European media and analysts tell us that the ECB does a great job and must infect its balance sheet more and more with debt from countries at risk. We have to print money and borrow more. Of course, they do not tell us that all that money will be paid by European citizens through taxes. But what they definitely never tell us is that if we inject risk, the weakness of the stabilization fund bond grows, becoming even less attractive for investors. Look at the graph below, which shows the differential of stability fund bond with the German bund, which has been rising enormously despite the positive messages from the friends of interventionism. Debt cannot be solved with more debt.

The solution

I repeat. A debt problem is not solved with more debt. A problem of liquidity, not solvency, as the present one is, will not be resolved in any other way than increasing revenue and reducing costs and through saving, which has plummeted by 11 points of GDP in Europe. But above all, by reducing costs, after the orgy of public spending of the past decade, shown in the graph below (courtesy http://blog.american.com and kpcb.com).

The solution is to maintain Europe focused on budgetary control, something that already exists in the treaties approved. No need to change anything, all that has to be done do is to comply with the treaties. Therefore, to cede fiscal and economic sovereignty to a European Union that has never reduced its budget and has no track-record of success in managing costs is ridiculous. I do not doubt at all that the peripheral countries, which have solved dozens of bigger problems, will be able to put their accounts in order, stop spending on stupid subsidies 3% of GDP per year, reduce bureaucracy and duplicated administrations and attract foreign capital.

The solution is that Europe learns once and for all that it’s more attractive to invest in countries that grow less but manage expenses according to their income than to finance a silly soup of subsidies that destroy jobs, GDP and competitiveness in the hope that markets forget, Eurobonds are issued and in a typical “greater fool theory” move, they can place the package of sub-prime debt to someone new.

The solution is to attract non-bank financing, private funding, which will be delighted to support the reconstruction process, and also to generate a legal, administrative and regulatory framework that is stable and efficient to make Europe a commercial partner not only between the EU countries, but for the rest of the world. Borrowing massively from each other to sell to each other is simply unsustainable.

From an economic and investment standpoint, it is suicidal for peripheral countries to cede sovereignty in their weakest moment just because they don’t want to make the necessary cuts. It is a “devil’s pact” that ties them to an organism with no better track-record than their own governments for decades just to keep, maybe for a few years, not more, the Roman Empire “bread and circus” policy of the lost decade we have lived.

Further:

Here is a link to my analysis of the Euro crisis and Spanish elections on CNBC http://video.cnbc.com/gallery/?video=3000058799